Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) is a flowering plant species of the Cucurbitaceae family and the name of its edible fruit. A scrambling and trailing vine-like plant, it is a highly cultivated fruit worldwide, with more than 1,000 varieties.

Watermelon is grown in favorable climates from tropical to temperate regions worldwide for its large edible fruit, which is a berry with a hard rind and no internal divisions, and is botanically called a pepo. The sweet, juicy flesh is usually deep red to pink, with many black seeds, although seedless varieties exist. The fruit can be eaten raw or pickled, and the rind is edible after cooking. It may also be consumed as a juice or an ingredient in mixed beverages.

Kordofan melons from Sudan are the closest relatives and may be progenitors of modern, cultivated watermelons.[2] Wild watermelon seeds were found in Uan Muhuggiag, a prehistoric site in Libya that dates to approximately 3500 BC.[3] In 2022, a study was released that traced 6,000-year-old watermelon seeds found in the Libyan desert to the Egusi seeds of Nigeria, West Africa.[4] Watermelons were domesticated in north-east Africa and cultivated in Egypt by 2000 BC, although they were not the sweet modern variety. Sweet dessert watermelons spread across the Mediterranean world during Roman times.[5]

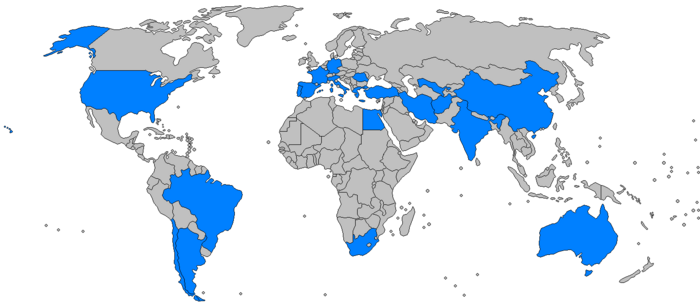

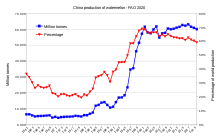

Considerable breeding effort has developed disease-resistant varieties. Many cultivars are available that produce mature fruit within 100 days of planting. In 2017, China produced about two-thirds of the world’s total of watermelons.[6]

Description

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The watermelon is an annual that has a prostrate or climbing habit. Stems are up to 3 metres (10 feet) long and new growth has yellow or brown hairs. Leaves are 60 to 200 millimetres (2+1⁄4 to 7+3⁄4 inches) long and 40 to 150 mm (1+1⁄2 to 6 in) wide. These usually have three lobes that are lobed or doubly lobed. Young growth is densely woolly with yellowish-brown hairs which disappear as the plant ages. Like all but one species in the genus Citrullus, watermelon has branching tendrils. Plants have unisexual male or female flowers that are white or yellow and borne on 40-millimetre-long (1+1⁄2 in) hairy stalks. Each flower grows singly in the leaf axils, and the species’ sexual system, with male and female flowers produced on each plant, is monoecious. The male flowers predominate at the beginning of the season; the female flowers, which develop later, have inferior ovaries. The styles are united into a single column.[citation needed]

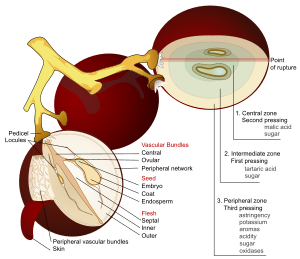

The large fruit is a kind of modified berry called a pepo with a thick rind (exocarp) and fleshy center (mesocarp and endocarp).[7] Wild plants have fruits up to 20 cm (8 in) in diameter, while cultivated varieties may exceed 60 cm (24 in). The rind of the fruit is mid- to dark green and usually mottled or striped, and the flesh, containing numerous pips spread throughout the inside, can be red or pink (most commonly), orange, yellow, green or white.[8][9]

A bitter watermelon, C. amarus, has become naturalized in semiarid regions of several continents, and is designated as a “pest plant” in parts of Western Australia where they are called “pig melon”.[10]

Taxonomy

The sweet watermelon was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753 and given the name Cucurbita citrullus. It was reassigned to the genus Citrullus in 1836, under the replacement name Citrullus vulgaris, by the German botanist Heinrich Adolf Schrader.[11] (The International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants does not allow names like “Citrullus citrullus“.)[12]

The species is further divided into several varieties, of which bitter wooly melon (Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai var. lanatus), citron melons (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides (L. H. Bailey) Mansf.), and the edible var. vulgaris may be the most important. This taxonomy originated with the erroneous synonymization of the wooly melon Citrullus lanatus with the sweet watermelon Citrullus vulgaris by L.H. Bailey in 1930.[13] Molecular data, including sequences from the original collection of Thunberg and other relevant type material, show that the sweet watermelon (Citrullus vulgaris Schrad.) and the bitter wooly melon Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai are not closely related to each other.[14] A proposal to conserve the name, Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai, was accepted by the nomenclature committee and confirmed at the International Botanical Congress in 2017.[15]

Prior to 2015, the wild species closest to Citrullus lanatus was assumed to be the tendril-less melon Citrullus ecirrhosus Cogn. from South African arid regions based on an erroneously identified 18th-century specimen. However, after phylogenetic analysis, the closest relative to Citrullus lanatus is now thought to be Citrullus mucosospermus (Fursa) from West Africa (from Senegal to Nigeria), which is also sometimes considered a subspecies within C. lanatus.[16] Watermelon populations from Sudan are also close to domesticated watermelons.[17] The bitter wooly melon was formally described by Carl Peter Thunberg in 1794 and given the name Momordica lanata.[18] It was reassigned to the genus Citrullus in 1916 by Japanese botanists Jinzō Matsumura and Takenoshin Nakai.[19]

History

Watermelons were originally cultivated for their high water content and stored to be eaten during dry seasons, as a source of both food and water.[20] Watermelon seeds were found in the Dead Sea region at the ancient settlements of Bab edh-Dhra and Tel Arad.[21]

Many 5000-year-old wild watermelon seeds (C. lanatus) were discovered at Uan Muhuggiag, a prehistoric archaeological site located in southwestern Libya. This archaeobotanical discovery may support the possibility that the plant was more widely distributed in the past.[3][20]

In the 7th century, watermelons were being cultivated in India, and by the 10th century had reached China. The Moors introduced the fruit into the Iberian Peninsula, and there is evidence of it being cultivated in Córdoba in 961 and also in Seville in 1158. It spread northwards through southern Europe, perhaps limited in its advance by summer temperatures being insufficient for good yields. The fruit had begun appearing in European herbals by 1600, and was widely planted in Europe in the 17th century as a minor garden crop.[8]

Early watermelons were not sweet, but bitter, with yellowish-white flesh. They were also difficult to open. The modern watermelon, which tastes sweeter and is easier to open, was developed over time through selective breeding.[22]

European colonists introduced the watermelon to the New World. Spanish settlers were growing it in Florida in 1576. It was being grown in Massachusetts by 1629, and by 1650 was being cultivated in Peru, Brazil and Panama. Around the same time, Native Americans were cultivating the crop in the Mississippi valley and Florida. Watermelons were rapidly accepted in Hawaii and other Pacific islands when they were introduced there by explorers such as Captain James Cook.[8] In the Civil War era United States, watermelons were commonly grown by free black people and became one symbol for the abolition of slavery.[23] After the Civil War, black people were maligned for their association with watermelon. The sentiment evolved into a racist stereotype where black people shared a supposed voracious appetite for watermelon, a fruit long associated with laziness and uncleanliness.[24]

Seedless watermelons were initially developed in 1939 by Japanese scientists who were able to create seedless triploid hybrids which remained rare initially because they did not have sufficient disease resistance.[25] Seedless watermelons became more popular in the 21st century, rising to nearly 85% of total watermelon sales in the United States in 2014.[26]

Systematics

A melon from the Kordofan region of Sudan – the kordofan melon – may be the progenitor of the modern, domesticated watermelon.[2] The kordofan melon shares with the domestic watermelon loss of the bitterness gene while maintaining a sweet taste, unlike other wild African varieties from other regions, indicating a common origin, possibly cultivated in the Nile Valley by 2340 BC.[2]

Composition

Nutrition

See also: Watermelon seed oil

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 127 kJ (30 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 7.55 g |

| Sugars | 6.2 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.4 g |

| Fat | 0.15 g |

| Protein | 0.61 g |

| showVitamins and minerals | |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 91.45 g |

| Lycopene | 4532 μg |

| Link to USDA Database entry | |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[27] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[28] | |

Watermelon fruit is 91% water, contains 6% sugars, and is low in fat (table).[29]

In a 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) serving, watermelon fruit supplies 125 kilojoules (30 kilocalories) of food energy and low amounts of essential nutrients (see table). Only vitamin C is present in appreciable content at 10% of the Daily Value (table). Watermelon pulp contains carotenoids, including lycopene.[30]

The amino acid citrulline is produced in watermelon rind.[31][32]

Varieties

A number of cultivar groups have been identified:[33]

Citroides group

(syn. C. lanatus subsp. lanatus var. citroides; C. lanatus var. citroides; C. vulgaris var. citroides)[33]

DNA data reveal that C. lanatus var. citroides Bailey is the same as Thunberg’s bitter wooly melon, C. lanatus and also the same as C. amarus Schrad. It is not a form of the sweet watermelon C. vulgaris nor closely related to that species.

The citron melon or makataan – a variety with sweet yellow flesh that is cultivated around the world for fodder and the production of citron peel and pectin.[34]

Lanatus group

(syn. C. lanatus var. caffer)[33]

C. caffer Schrad. is a synonym of C. amarus Schrad.

The variety known as tsamma is grown for its juicy white flesh. The variety was an important food source for travellers in the Kalahari Desert.[34]

Another variety known as karkoer or bitterboela is unpalatable to humans, but the seeds may be eaten.[34]

A small-fruited form with a bumpy skin has caused poisoning in sheep.[34]

Vulgaris group

This is Linnaeus’s sweet watermelon; it has been grown for human consumption for thousands of years.[34]

- C. lanatus mucosospermus (Fursa) Fursa

This West African species is the closest wild relative of the watermelon. It is cultivated for cattle feed.[34]

Additionally, other wild species have bitter fruit containing cucurbitacin.[35] C. colocynthis (L.) Schrad. ex Eckl. & Zeyh., C. rehmii De Winter, and C. naudinianus (Sond.) Hook.f.

Varieties

The more than 1,200[36] cultivars of watermelon range in weight from less than 1 kilogram (2+1⁄4 pounds) to more than 90 kg (200 lb); the flesh can be red, pink, orange, yellow or white.[37]

- The ‘Carolina Cross’ produced the current world record for heaviest watermelon, weighing 159 kg (351 lb).[38] It has green skin, red flesh and commonly produces fruit between 29 and 68 kg (65 and 150 lb). It takes about 90 days from planting to harvest.[39]

- The ‘Golden Midget’ has a golden rind and pink flesh when ripe, and takes 70 days from planting to harvest.[40]

- The ‘Orangeglo’ has a very sweet orange flesh, and is a large, oblong fruit weighing 9–14 kg (20–31 lb). It has a light green rind with jagged dark green stripes. It takes about 90–100 days from planting to harvest.[41]

- The ‘Moon and Stars’ variety was created in 1926.[42] The rind is purple/black and has many small yellow circles (stars) and one or two large yellow circles (moon). The melon weighs 9–23 kg (20–51 lb).[43] The flesh is pink or red and has brown seeds. The foliage is also spotted. The time from planting to harvest is about 90 days.[44]

- The ‘Cream of Saskatchewan’ has small, round fruits about 25 cm (10 in) in diameter. It has a thin, light and dark green striped rind, and sweet white flesh with black seeds. It can grow well in cool climates. It was originally brought to Saskatchewan, Canada, by Russian immigrants. The melon takes 80–85 days from planting to harvest.[45]

- The ‘Melitopolski‘ has small, round fruits roughly 28–30 cm (11–12 in) in diameter. It is an early ripening variety that originated from the Astrakhan region of Russia, an area known for cultivation of watermelons. The Melitopolski watermelons are seen piled high by vendors in Moscow in the summer. This variety takes around 95 days from planting to harvest.[46]

- The ‘Densuke’ watermelon has round fruit up to 11 kg (24 lb). The rind is black with no stripes or spots. It is grown only on the island of Hokkaido, Japan, where up to 10,000 watermelons are produced every year. In June 2008, one of the first harvested watermelons was sold at an auction for 650,000 yen (US$6,300), making it the most expensive watermelon ever sold. The average selling price is generally around 25,000 yen ($250).[47]

- Many cultivars are no longer grown commercially because of their thick rind, but seeds may be available among home gardeners and specialty seed companies. This thick rind is desirable for making watermelon pickles, and some old cultivars favoured for this purpose include ‘Tom Watson’, ‘Georgia Rattlesnake’, and ‘Black Diamond’.[48]

Variety improvement

Charles Fredrick Andrus, a horticulturist at the USDA Vegetable Breeding Laboratory in Charleston, South Carolina, set out to produce a disease-resistant and wilt-resistant watermelon. The result, in 1954, was “that gray melon from Charleston”. Its oblong shape and hard rind made it easy to stack and ship. Its adaptability meant it could be grown over a wide geographical area. It produced high yields and was resistant to the most serious watermelon diseases: anthracnose and fusarium wilt.[49]

Others were also working on disease-resistant cultivars; J. M. Crall at the University of Florida produced ‘Jubilee’ in 1963 and C. V. Hall of Kansas State University produced ‘Crimson Sweet’ the following year. These are no longer grown to any great extent, but their lineage has been further developed into hybrid varieties with higher yields, better flesh quality and attractive appearance.[8] Another objective of plant breeders has been the elimination of the seeds which occur scattered throughout the flesh. This has been achieved through the use of triploid varieties, but these are sterile, and the cost of producing the seed by crossing a tetraploid parent with a normal diploid parent is high.[8]

As of 2017, farmers in approximately 44 states in the United States grew watermelon commercially, producing more than $500 million worth of the fruit annually.[50] Georgia, Florida, Texas, California and Arizona are the United States’ largest watermelon producers, with Florida producing more watermelon than any other state.[51][50] This now-common fruit is often large enough that groceries often sell half or quarter melons. Some smaller, spherical varieties of watermelon—both red- and yellow-fleshed—are sometimes called “icebox melons”.[52] The largest recorded fruit was grown in Tennessee in 2013 and weighed 159 kilograms (351 pounds).[38]

Uses

Culinary

Watermelon is a sweet, commonly consumed fruit of summer, usually as fresh slices, diced in mixed fruit salads, or as juice.[53][54] Watermelon juice can be blended with other fruit juices or made into wine.[55]

The seeds have a nutty flavor and can be dried and roasted, or ground into flour.[9] Watermelon rinds may be eaten, but their unappealing flavor may be overcome by pickling,[48] sometimes eaten as a vegetable, stir-fried or stewed.[9][56]

Citrullis lanatus, variety caffer, grows wild in the Kalahari Desert, where it is known as tsamma.[9] The fruits are used by the San people and wild animals for both water and nourishment, allowing survival on a diet of tsamma for six weeks.[9]

Symbolic

The watermelon is used variously as a symbol of Palestinian resistance,[57][58][59] of the Kherson region in Ukraine, and of eco-socialism, as in ‘green on the outside, red on the inside’. Because it is mostly water, the watermelon has been used to symbolize abrosexuality, a “fluid” or changing sexual orientation.[60][61] In the United States, the watermelon has also been used as a racist stereotype associated with African Americans.[62]

Cultivation

Watermelons are plants grown from tropical to temperate climates, needing temperatures higher than about 25 °C (77 °F) to thrive. On a garden scale, seeds are usually sown in pots under cover and transplanted into the ground. Ideal conditions are a well-drained sandy loam with a pH between 5.7 and 7.2.[63]

Major pests of the watermelon include aphids, fruit flies, and root-knot nematodes. In conditions of high humidity, the plants are prone to plant diseases such as powdery mildew and mosaic virus.[64] Some varieties often grown in Japan and other parts of the Far East are susceptible to fusarium wilt. Grafting such varieties onto disease-resistant rootstocks offers protection.[8]

The US Department of Agriculture recommends using at least one beehive per acre (4,000 m2 per hive) for pollination of conventional, seeded varieties for commercial plantings. Seedless hybrids have sterile pollen. This requires planting pollinizer rows of varieties with viable pollen. Since the supply of viable pollen is reduced, and pollination is much more critical in producing the seedless variety, the recommended number of hives per acre increases to three hives per acre (1,300 m2 per hive). Watermelons have a longer growing period than other melons and can often take 85 days or more from the time of transplanting for the fruit to mature.[37] Lack of pollen is thought to contribute to “hollow heart” which causes the flesh of the watermelon to develop a large hole, sometimes in an intricate, symmetric shape. Watermelons suffering from hollow heart are safe to consume.[65][66]

Farmers of the Zentsuji region of Japan found a way to grow cubic watermelons by growing the fruits in metal and glass boxes and making them assume the shape of the receptacle.[67] The cubic shape was originally designed to make the melons easier to stack and store, but these “square watermelons” may be triple the price of normal ones, so appeal mainly to wealthy urban consumers.[67] Pyramid-shaped watermelons have also been developed, and any polyhedral shape may potentially be used.[68]

Watermelons, which are called tsamma in Khoisan language and makataan in Tswana language, are important water sources in South Africa, the Kalahari Desert, and East Africa for both humans and animals.[69]

Production

In 2020, global production of watermelons was 101.6 million tonnes, with China (mainland) accounting for 60% of the total (60.1 million tonnes).[6] Secondary producers included Turkey, India, Iran, Algeria and Brazil – all having annual production of 2–3 million tonnes in 2020.[6]

| Watermelon production, 2020 (millions of tonnes) | |

|---|---|

| 60.1 | |

| 3.49 | |

| 2.79 | |

| 2.74 | |

| 2.29 | |

| 2.18 | |

| World | 101.6 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[6] | |

Gallery

- Watermelon cubes

- Watermelons with dark green rind, India

- Watermelon flowers

- Watermelon leaf

- Flower stems of male and female watermelon blossoms, showing ovary on the female

- Watermelon plant close-up

- Watermelon baller

- Watermelon with yellow flesh

- ‘Moon and stars’ watermelon cultivar

- Watermelon and other fruit in Boris Kustodiev‘s Merchant’s Wife

- Watermelon for sale

- Watermelon out for sale in Maa Kochilei Market, Rasulgarh, Odisha, India

- Watermelon grown in Buryatia, Siberia

- Watermelon rind curry

- Roasted and salted watermelon seeds

- Watermelon seed under a microscope

- Watermelon, sliced into pieces

- Very ripe Sugar Baby watermelon, grown in Oklahoma, bursts open when a small incision is made into its rind

- Watermelon with yellow flesh

- Ice pop